Now may I give an imaginary lesson to a class of children of let us say, seven to nine. In such a class I should read the Bible aloud, the children following in their own books, or, the younger ones, merely listening. A very little time ago I took the Parable of the Sower with children of just this age.

First of all I should connect with last week's lesson. This is best done by asking a question or two—broad questions, simply asked to see whether the children remember the story, whether it is all still fresh in their memory. This should take perhaps two minutes. Then a very short, vivid description of the scene of the Parable; the spring of the year, the gay garments of the crowd, the sower perhaps in the distance. (May I interrupt myself here and say that one of the very best ways of getting the children to visualise the scene is to tell them to shut their eyes, then vividly and shortly describe the scene—say for instance: A hot, blue sky, golden corn, with poppies and a sandy path through the field—now, children can you see it?

The scene they call up is better than a picture, far, far better than the blackboard sketch, and has many other merits.) This introduction must be short, and no things are shown to the children—such as grains of corn, for example. Such things only distract them from the main theme. Then all the children—except those who cannot read at all—open their Bibles, and the teacher reads the story aloud, slowly and as beautifully as she can, as if it were quite the most interesting thing he or she had ever read. At the end of the parable (I should not read the explanation now) the teacher turns to any child: "Tommy, will you begin to tell the story I have just read? See how much of the very Bible words you can remember." He begins, and after a few sentences the teacher turns to some other child: "Now Mary, what happened next?" and so on till the story is finished. All the children will, if the class is small, get a chance of "narrating,' as we call it, but no child knows when he may not be called on and all will listen eagerly to see if Tommy or Mary leaves out anything. During this "narration" the teacher listens, and cheers on with her visible interest. She does not interrupt, does not even correct, but if a narrator goes wrong, she can turn to another child and say, "Can you remember what happened next?"

The narration over, there comes that so important part of all Scripture lessons, the "new thought of God" to be learnt. The teacher will ask this child or that, "Who do you think the Sower was?" and "What then is the seed?" Perhaps you think this too difficult for such young children? Remember, they are cleverer than their teacher! But the teacher has more experience, and will guide the children rightly, and after some little discussion, she can tell the children that there is something particularly wonderful about this parable, for we have Christ's own interpretation of it. She will then read it, as before, without interruption, without talk, and at the end, other children will be called upon to narrate this too, just as they did the story itself.

This parable is so full of lessons for us to take to heart and ponder over, that it will be easy for the children to find many, with the very smallest amount of help from the teacher. In some cases, of course, this most important part of the lesson must come from the teacher; but children remember best, ponder over more, what they have discovered for themselves. Again, sometimes it is wise to re-read the Bible portion at the end of the lesson—if for instance there has been so animated a discussion that the sacred words are clouded by the mist of talk. Then next Sunday the teacher might begin: "Last week we read about the Sower and his seeds, can anyone remember one kind of soil the seed fell on?" I know a crowd of small arms would rise, and the wise teacher would choose a child who had been a little silent perhaps last week. For care must be taken in a large class that every child has a turn in course of time.

It is nothing less than wonderful how lessons given in this way are remembered from week to week. Children that I have taught often remember, far better than I do, the lesson they had from me—I should say with me—a week ago. This is natural, for they did the work; I listened and cheered on; they had to concentrate their whole minds on the story; in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, it would only be read once, and then, in the narration, what concentration is needed! Try for yourselves; read a page or two of an interesting book, and then narrate it to yourself. It is not memory; it is concentrated attention, and if you did it constantly you would be amazed how your powers of concentration would increase. But you read only once, remember!

You will have noticed that, except at the beginning of the lesson, there is no questioning. Instead of being continually egged on by leading questions, or irritated by niggly questions, the child tells you the lesson all by himself; certainly no more sure test of knowledge could be demanded. None of us knows a thing till we can tell all about it; if we want to know something thoroughly we, unconsciously perhaps, narrate it to ourselves, constantly answering the reiterated question, "What came next?, What came next?" Do you see how a child's vocabulary increases who "narrates"?

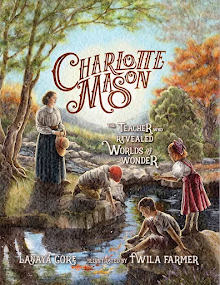

No more set answers to set questions, no more jerky monosyllables, but a good, flowing account of what was read in good English—you remember they narrate "in the Bible words as much as possible"—and what finer English is there? Then also you will have noticed that there were no fascinating objects for the children to look at. They know what corn is like, and any country child has seen a sower sowing. But they should visualise the scene. And Mr. Fisher said, you remember, that a child has more imagination than a grown-up. If an illustration or explanation of something is needed, we use the bit of india rubber, the ruler and pencil that are lying about, and a few words and the children's imagination fills in the rest. And what about pictures? A good one—Millais' "Sower" is beautiful—may be sometimes a help, but what child wants a picture of Daniel in the Lions' Den, of Saul escaping in the basket, and so on?

The Sower by Sir John Everett Mallais published 1864

It's interesting to me that she doesn't recommend very many visual aids. The child's imagination is sufficient with maybe a drawing on the blackboard or maybe a good picture. Younger children would enjoy acting out this parable also which is another form of narration. I would be tempted to add all sorts of crafty ideas involving bird seed or something. :-) But I don't think that would be in line with these ideas. One more post to come to complete the article!

4 comments:

Lanaya, I, too, would be tempted to add "crafty" ideas and other visuals. That is what we have been told that makes an interesting lesson and one a good teacher. And yet how I remember the vivid "video" that played out in my mind when I listened to radio programs as a child. Will wait for the next installment. Thanks, Elayne

I love the the idea too! I think we under estimate children and the way they relate to words. I just recently read Hinds feet in High places to my boys for our morning narration. They loved it! No pictures just the words painting them in their minds.

good story telling can be amazing and is a lost art. I can remember reading to my kids in the evening and trying to be really animated in it, and how much we all enjoyed it. I remember reading Riki Tiki Tavi by Rudyard Kipling and how fixated they were just by the imaginations at work.

Bruce

good story telling is a lost art, and is very effective-- even in this day. When I help with pre-schoolers at church, they just hang on every word when you tell a story that is animated and brought to life.

Post a Comment